Thank you for coming with us on this journey through Danish design. One of the things that came up again and again in my conversations was the notion of co-creation. And what is co-creation, you ask? In a way it's a collaboration - you invite a diverse group of people with different knowledge and talents into a room and everyone contributes to solving the task at hand. Everyone’s unique perspective is taken into account and the solution is thereby co-created.

Co-creation is something that Danish design and Danish culture in general are very good at. One of the best-known examples is LEGO’s Ideas platform. Anyone who wants to, can build a LEGO set, upload it to the platform and suggest that LEGO make it as a real set. If they can gather 10,000 votes for their idea, LEGO will consider making it.

This way, LEGO has gotten ideas for sets they would never have come up with or pursued on their own. And in return for the great ideas, they share the wealth with the person who suggested the set, giving them part of the revenue. This has resulted in cool smaller sets like the space-themed Exo-Suit by Peter Reid and the Research Institute promoting women in STEM by Ellen Kooijman, as well as more famous sets like Central Perk from the t.v. show Friends or the house from Home Alone. They all exist thanks to co-creation.

*Please note that the text on this page is a transcript of the podcast episode.

Co-creation makes a difference for B&O

Lise Thomsen from the Confederation of Danish Industry told us about how Danish design giant Bang & Olufsen uses co-creation in their design process.

Lise: I actually made an interview with a designer from Bang & Olufsen. First he says that Bang & Olufsen is the only sound company in Europe that is on its own that still owns themselves.

It's not a part of a huge Japanese concern.

Julie: ...of a huge conglomerate. They stayed independent.

Lise: It's yeah, they are independent and that's because of design and then he described the design process as a process where everybody is part of this process and everybody is asked. So they will contribute within this process, and they contribute to create the best product ever. And they will not stop until everybody feels like they have contributed with the best they can.

Julie: Amazing that Bang & Olufsen sees their design process as a big part of what has helped them remain an independently owned maker of high end quality Danish design sound products. It also results in some very beautiful Danish design.

Photo credit: Bang & Olufsen

Data Mirror co-created art project

But let’s have a look at another kind of co-creation project.

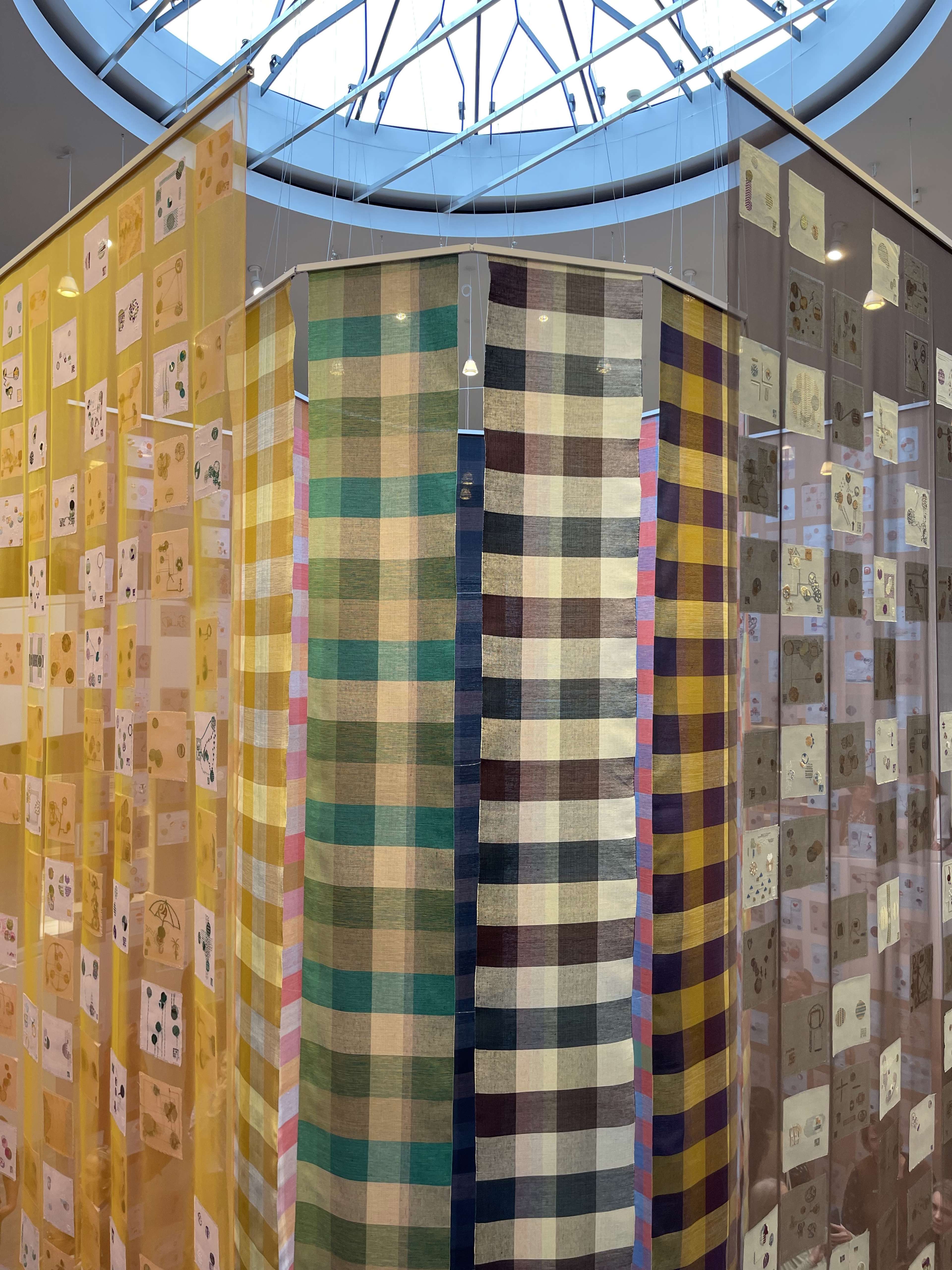

Trapholt Museum of Modern Art and Design in Kolding has a reputation for doing ambitious co-creation projects. Artist and weaver Astrid Skibsted created one of these projects for Trapholt last year.

It’s called Data Mirror. The project invited the public to use their Facebook data to create an embroidered snapshot of what it said about them. Astrid chose the overall colour scheme and created a model that combined weaving and its principles with the data and then more than 600 people got to work on their own online data, transforming it into cloth and thread.

Photo credit: Julie Broberg

Data Mirror at Trapholt Museum

Panels of embroidery and weaving

The woven panels were done by various weavers and weaving groups

The work is disiplayed in a magnificent round room with a staircase all around

Co-creating with more than 600 people

Astrid: You really invite people into a process and make and make them an important part of the initial exhibition that's going to be in the end, but the process is actually the project, right? I mean it's the way we meet each other and explore. Explore…I mean in this case it was our data and how we can combine that and talk about that and learn…learn something about this whole part of our world that data is. But doing so through our craft.

Julie: So somehow making that data tangible.

Astrid: Making it tangible and also talking about it through a language of craft where we are at least this group of people participating here, they had craft as a safe space and something that is well known to them and also combining it with the data language and both the embroidery and weaving which we used in this project, it has like a binary language. I mean the loom was a computer before there was a loom before there was a computer, I mean.

And so we already know this, this language...

Julie: Zeros and the ones....

Astrid: …the zeroes and the ones and and we have the right to…to have a voice within this technical world, a lot of people wouldn't normally have looked at this personal data and actually given it like a thought...it's something that you feel repelled from almost.

But here working with it also together in this group, where it was safe to say, “I don't know anything.” But we're exploring it and we're learning it as we go along and also in order to be able to be part of the conversation in general and say, "hey, I have actually talked, I've actually looked into my own data. I have embroidered them, now I understand them like this."

Julie: I found out that these are the words that I often write on Facebook.

Astrid: It’s also looking at what was interesting in the data, what actually can I recognise myself from, from these traces that I leave? But I think what was most important was for people to have the experience of, "I have a right to say something about this topic and I have a voice. And I have all these amazing skills within crafts and textiles that is a language to talk about this topic."

So that was what the project was also about. Because co- creating is not about like just having everyone do what they want to do.

Julie: No, you need to have a framework.

Astrid: In order for it to actually also in the end…for this process to become a work of art.

Rocks of Greenland at Design Museum Denmark

Data Mirror isn’t the only co-creation project that Astrid has been involved in. Much of her work is a collaboration with other artists and people from other fields of study - like anthropology and even mining.

Astrid: I'm currently exhibiting at the Design Museum in Copenhagen, where we have this exhibition called Rocks of Greenland, which is n anthropologist and she has done research in Greenland in gold mines and ruby mines, and working with what happens when we take the natural resources out of the ground and out of the mountain. And what happens with people, with politics, with nature in this process? And that's just incredibly complex.

Julie: But how did you weave with rocks? Rocks of Greenland?

Astrid: Well you can't weave with rocks, but she's really good in a way that she likes to have her research become physical. She gathered a lot of objects from these mines, like over the years, a lot of tools and working gear and clothes and helmets and wires and all these objects. Also, samples from the mountain you have these drilling samples where you drill for the gold, where is the gold actually, so where should we...? Like core samples of the rock where you can see the beautiful layers of the rock and the colors.

Can you weave the inside of a mine?

Astrid: When you when you gather things out of a mine, everything is really dirty. There's sort of this rub off of both like the mountain that's been blown to pieces and ground into almost like flour in order to get this gold out. Everything is so dusty and so dirty, so both like the nature and the people and the tools they sort of rub off on each other. I mean and there's nothing is clean.

There’s like this rub off of materials and there's one story there. But she wanted me to sort of…can you…can you weave this process? Can you weave this mountain? So that we can show it together with all these objects from the mine and then also with Nikolai Appel’s jewelry that is made from Greenland gold.

But we didn't as much want to talk about that actually - the jewels and the rubies so much as the process in order to get them.

So then it becomes my job to sort of do that and can you weave the inside of a mine?

And you can weave anything.

Julie: Wow!

Astrid: You can weave anything. Yes, I feel that's true.

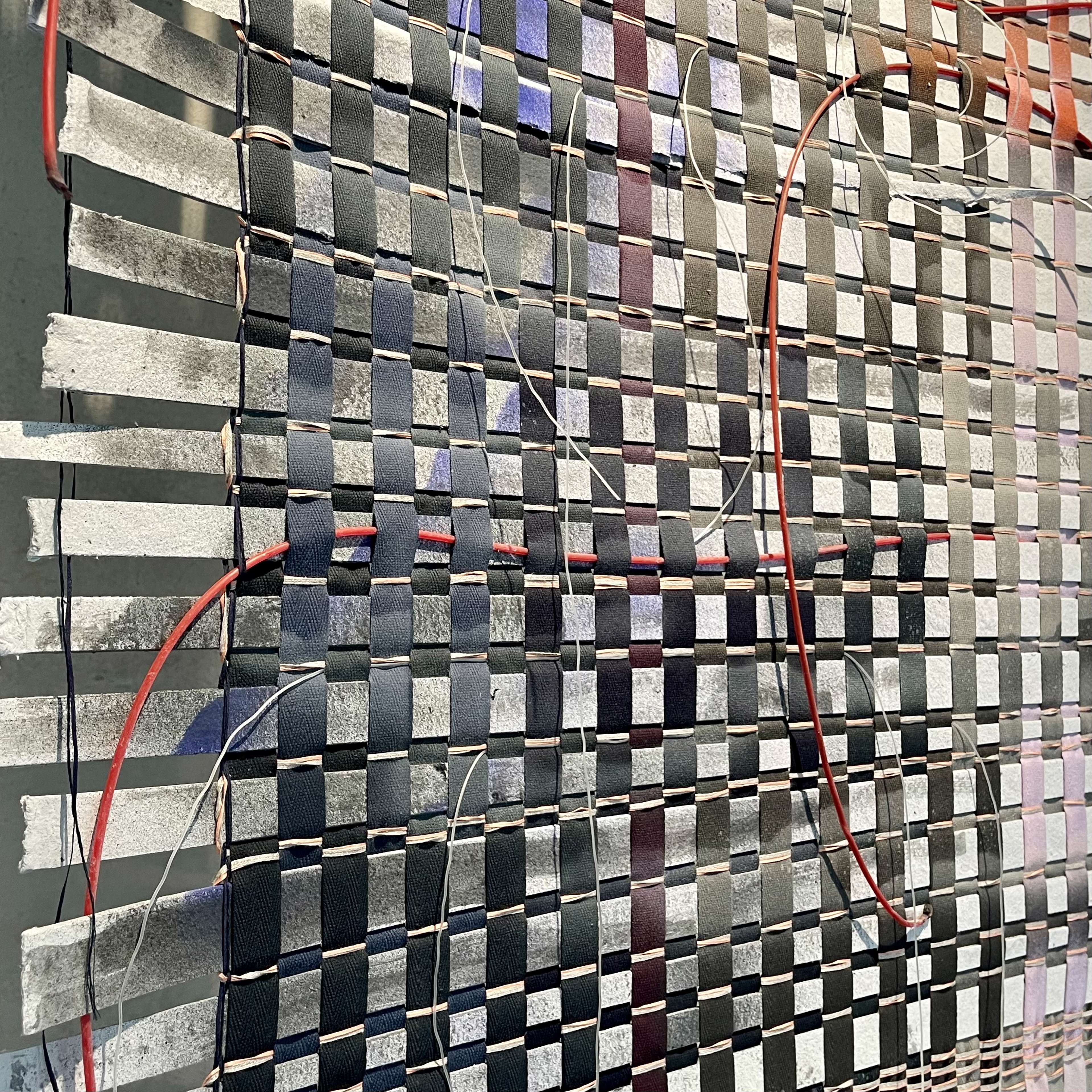

Rocks of Greenland

Astrid used different materials and techniques to achieve the dustiness of the mountain.

Core samples from the mine.

Some of the works include blast wires from the mine.

Smaller pieces capture the way the mine is blown to pieces.

You can't weave with a rock

Astrid: And I went to visit Natalia, the anthropologist, and her piles and piles of stuff, to go through that and find inspiration. So how do we actually do that? And what I ended up doing was sort of combining the mountain. I could see these core samples of the rocks like because I can't weave with that. You can't weave with a rock. But you can you can take the the colours and like these layers in the rock and the lines.

These lines and layers and translate that into textiles and found material that sort of had that same quality. That same kind of dryness. Dustiness, yeah. I used a lot of spray paint on my yarns and on my warp in order to get this in the process.

Julie: After or before weaving?

Astrid: In the process. Before weaving, so that I could get the right feeling of this during the process...the dusty chunky mountain rock, but also the beauty of it.

And then on the other hand, I had these textiles, these leftovers...

Julie: So like the like safety clothing?

Astrid: Clothing. Yeah, like work clothing and like, in the beginning, I thought I was going to weave directly with that. But it it didn't really work. It needed to sort of be translated. And it became like too cartoonish to just have work wear woven in and it didn't work.

You try everything and then I also kind of translated that and the colours and the reflex like you have on the safety wear, and neon yellow and orange. So I wove that in on the other end so that when you see these textiles and they're quite large and also very large scale pixels like the woven pixel is like 2 by 2 centimeters.

Julie: Are they quite open?

Astrid: No, they're quite dense. And it looks like very large pixels. And then in a way like the woven structure sort of becomes the the rock that's exploded.

Because you can see that it's sort of blown to pieces.

Julie: Wow!

Astrid: So the weaving itself became the story that this mountain is scattered into pieces.

Julie: It's actually destroyed.

Materials from the mine

Astrid: Yeah, and but also the the workers doing this work, they go into the mine like they like you can really see like how the clothes like it's all patched up as well they sew like little patches. There's all this repair work on there.

Julie: Interesting.

Astrid: And it's quite beautiful. And then also translating that into textiles and then weaving that together, the only thing that actually came from the mine that I wove directly in was this detonator thread.

Julie: OK, is it a kind of wire?

Astrid: It's a kind of wire. They're bright yellow, bright pink - they're plastic, plastic-coated, and they have been used in the blasting, of dynamite in the mountains, you have these plastic wires that sort of get blown up and I wove them directly into the mountain.

Once you're done like it's, it becomes sort of a leftover plastic waste that's sort of lying there between all the rocks.

Julie: And they don't gather it up.

Astrid: They don't gather it. You don't collect the leftover waste from from a mining project like this because it's too expensive. So they just leave it. So, but then we took some of it and wove it in into these pieces. And so that then becomes the story of this mining, what it means to to gather resources...

Julie: Embodied in cloth...

Astrid: So it's sort of like a woven mountain and it makes sense when you see it, I feel. But that's also a process you don't know until you do it so.

Julie: That's amazing. It's an amazing co-creative project.

It’s not too late to see both exhibitions featuring Astrid’s work. Data Mirror is at Trapholt in Kolding through November 5th and Rocks of Greenland can be seen at Design Museum Denmark in Copenhagen through April 2024. So, if you’re in Denmark, they are definitely worth a visit. Both museums will further whet your appetite for Danish design.

As you know by now, we are a kitchen company, so we always have to talk a bit about kitchens at the end. Sune Kjems from the Danish Design Council told us a story about his personal evolution in the kitchen and how co-creation played a role in that…

Co-creating in the kitchen with friends

Sune: I love to cook myself. And my personal evolution has gone from like, really preparing and standing in the kitchen for hours and hours to create this art piece, and to kind of serve it and hope for some kind of applause. And making it extremely stressful and pissing my family off. To much more, bring what you got and we will co-create this dinner.

Julie: Amazing.

Sune: And it's so much more fun. And it always ends up with the most amazing dinner. And you can put a theme to it…I've invited some friends to make spring rolls. None of us are experienced in making spring rolls, but let's make spring rolls.

Julie: Do you make them together in your kitchen or everybody brings some that they've made?

Sune: No, we make them together and we make a lot and too much because then we can bring them back to our families so we combine our different spring rolls…and kitchens have the opportunity with these kitchen islands to just gather around and co-create. So I think it's an amazing platform for yeah, for doing something together that is extremely meaningful right now, but also in a bit longer perspective. The kitchen is in many homes the central or the center, so it just in its design invites you to gather around, talk, snack, have a drink.

Julie: For sure it's sociable. it's a social space, right?

Sune: You wouldn’t be able to do it in old school kitchens. So that's absolutely in the design of it, but it's also don't take yourself so ******* seriously.

Julie: What a great note to end on. I love it. That's the perfect note to end on. Amazing!

Photo credit (and a recipe): Woks of Life

I find co-creation to be one of the most exciting aspects of Danish design that we’ve explored so far and I hope you do too. In fact, our next episode will also be about co-creation. And I definitely want to invite my friends over for a co-created dinner one day very soon, don’t you?

It seems like ideas are at their best and most surprising when you share them and when your own ideas mix with other people’s ideas. In our next episode, we’re going to talk about exactly that with furniture designer Lærke Ryom. Be sure you’re subscribed, so you don’t miss out! And if you could rate and review us on Apple Podcasts, we would be very grateful for that!

And I have to leave you with another podcast recommendation. Back in our first episode, we mentioned that the most famous icon of Danish design, the Sydney Opera House, is turning 50 this year. The podcast Cautionary Tales did a recent episode on the whole saga of how Jørn Utzon’s design was chosen and how it got built. I had no idea it was such a harrowing tale. Look for it whenever you listen to podcasts - it’s called “A Chorus of Contempt at the Sydney Opera House” and it’s in the Cautionary Tales feed.

Thank you for listening!

Featured in this episode

Lise Thomsen

Confederation of Danish Industry

Astrid Skibsted

Textile Designer

Sune Kjems

Founding partner, Via Design